STORE

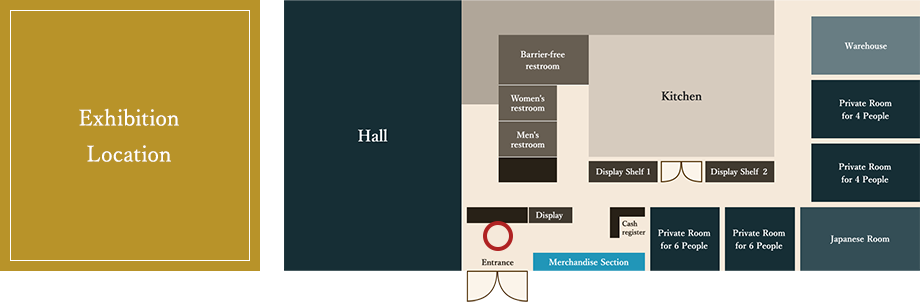

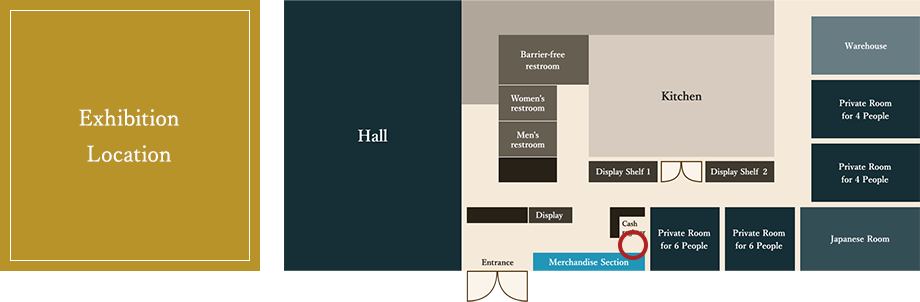

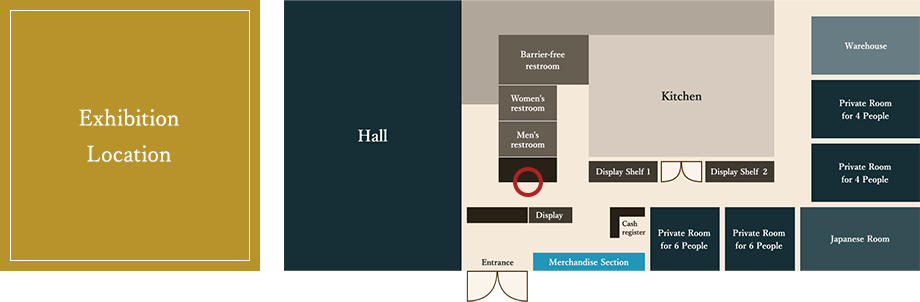

Floor Guide

Yame Handmade Japanese Paper

(Chinaberry used for

the frames)

This paper is very durable. It is said that this paper began to be made more than 400 years ago, when Nichigen, a monk from Echizen, found that the Yabe River's geography and water quality were suitable for papermaking, and taught the local people how to make paper.

Jyojima Onigawara

The history of Jyojima Onigawara or goblin-mask tiles started when the Arima family took over control of the Kurume domain. Recognized for their beautiful gloss, refined shapes and extraordinary durability, the Jyojima Onigawara have been widely used to ward off evil in shrines, temples and traditional Japanese houses across the Kyushu region.

Kurume Kasuri Textile

A bundle of cotton threads is tied with a hemp rope and dyed with indigo to create a mottled pattern. The threads of that bundle are woven into threads from another bundle with a different pattern to produce textile with a wide variety of patterns. Kurume Kasuri, invented in the Edo period by the daughter of the rice merchant Den Inoue, is now loved by many people as a representative example of Japanese kasuri culture.

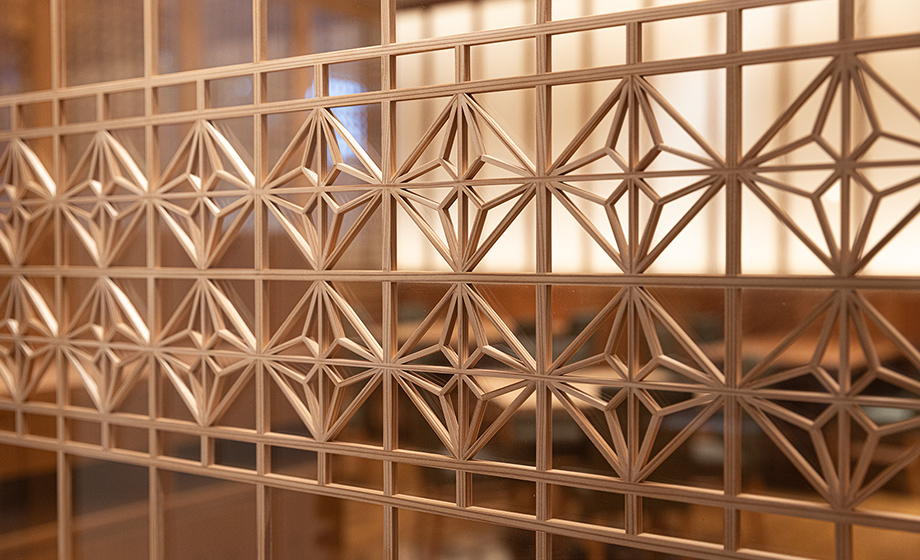

Okawa Kumiko Openwork(Door)

Boasting a history of approximately 300 years, this openwork comes in more than 200 patterns resulting from an assembly of wooden sticks. The openwork looks fragile, but since the components are assembled precisely to engage with one another, it is actually as sturdy as a single plate.

Hakataori Textile

Hakataori, a thick textile featuring fusenmon and ryujyo patterns, dates back approximately 780 years, after some Japanese mastered a textile production technique in China, introduced it into Japan, and improved upon it. A man’s obi (sash) of the textile is especially highly regarded because the obi does not loosen until the evening after it is tied in the morning. This obi is the best example demonstrating the properties of this textile, with silk threads being painstakingly and robustly woven into the fabric.

Yame Garden Lantern

This stone lantern is made of tuff, which is mined in abundance in the local area. The stone is light, soft, and easily weathered, but is resistant to cold and heat and gathers stone moss (moss growing on stone surfaces) quickly, making it suitable as a material for garden lanterns.

Kokura Textile

This is a thick, durable, and smooth cotton textile. Using thread dyed in advance, weaving is performed so that the warp will be arranged more densely than the weft. This enables striped patterns to be formed on the textile. The color shades of the patterns exude a dignified, crisp atmosphere and produce a three-dimensional effect.

Okawa Kumiko Openwork

Boasting a history of approximately 300 years, this openwork comes in more than 200 patterns resulting from an assembly of wooden sticks. The openwork looks fragile, but since the components are assembled precisely to engage with one another, it is actually as sturdy as a single plate.

Kakegawa Rug(Tatami)

This rug has long been produced throughout the Chikugo region, known as a rush production center. Featuring rush’s distinctively refreshing scent and vivid color, the rug produces a dignified atmosphere and serves as a special attraction of summer in the region.

Yame Bamboo Blind

Made of thin bamboo sticks, this blind was an essential item to partition a room in a shinden style structure in the Heian period. Today, it is still used as luxury furnishing in Japanese houses, shrines, and temples.

Yame Handmade Japanese Paper

(Chinaberry used for

the frames)

This paper is very durable. It is said that this paper began to be made more than 400 years ago, when Nichigen, a monk from Echizen, found that the Yabe River's geography and water quality were suitable for papermaking, and taught the local people how to make paper.

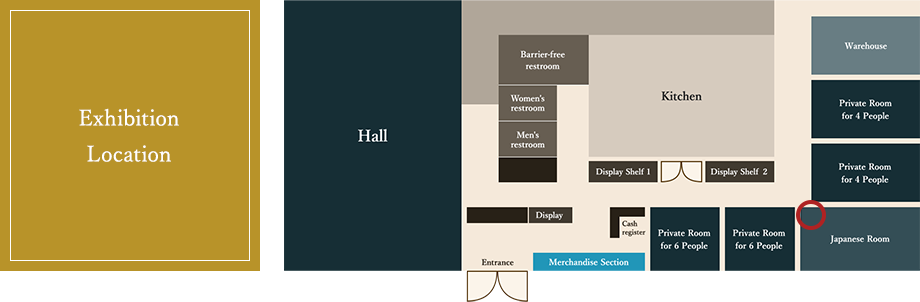

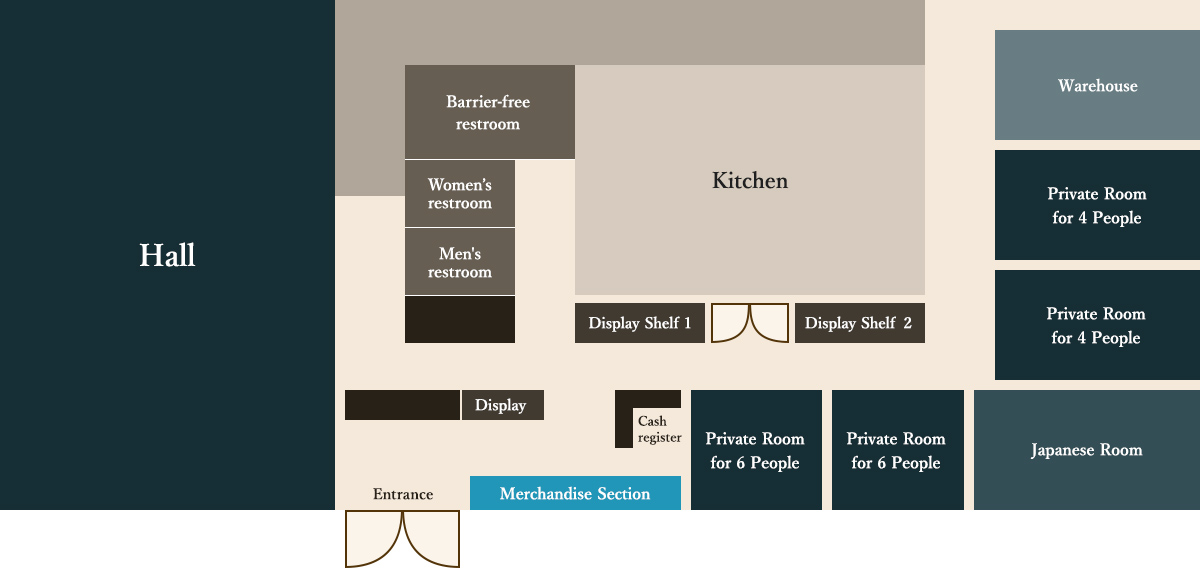

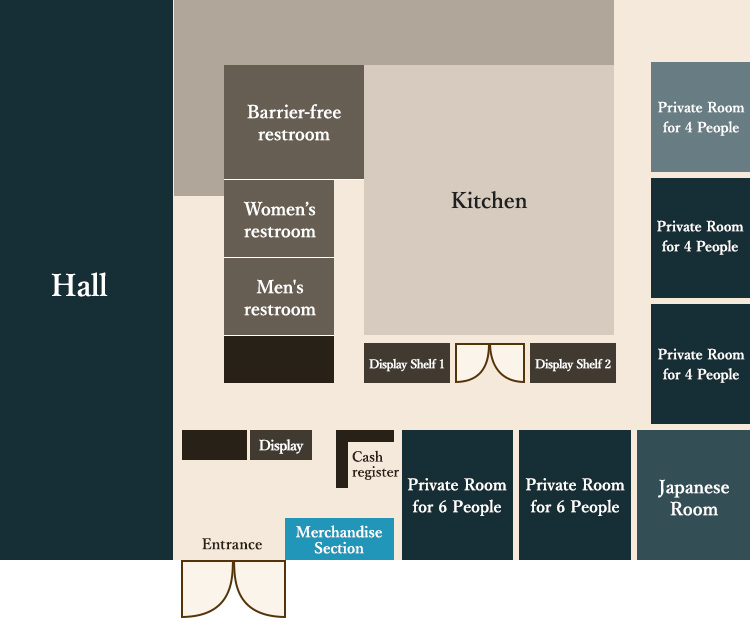

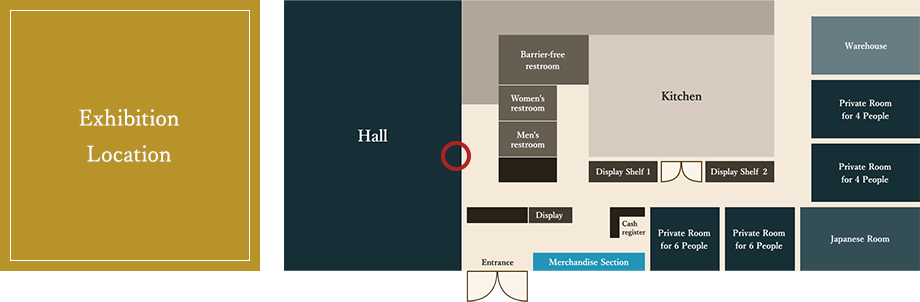

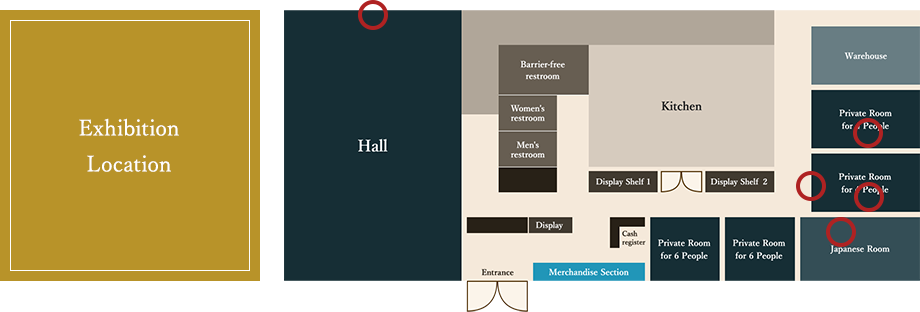

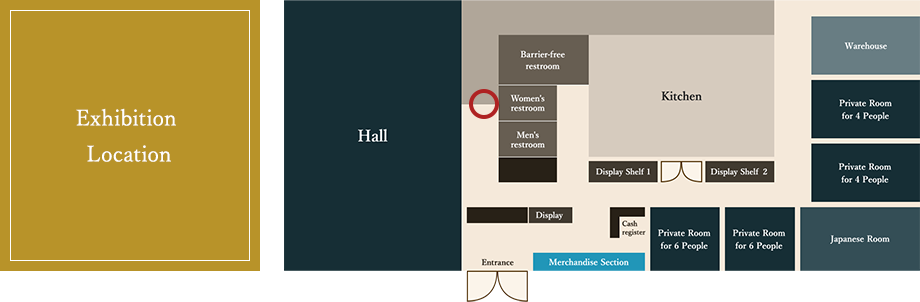

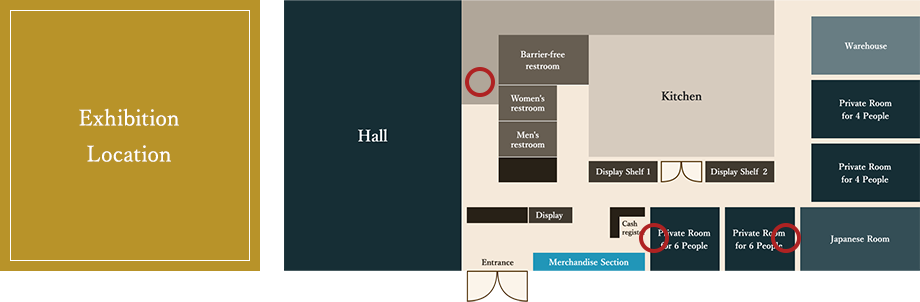

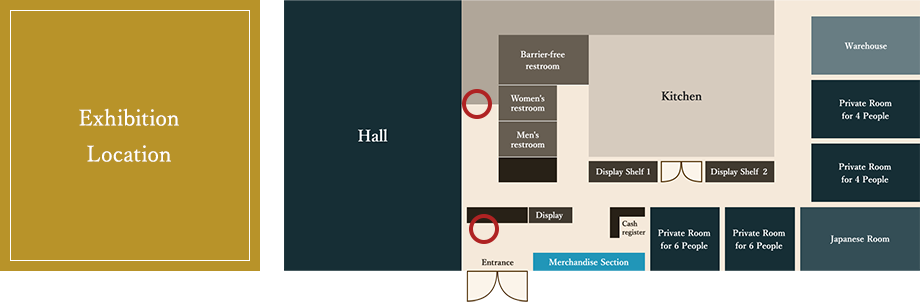

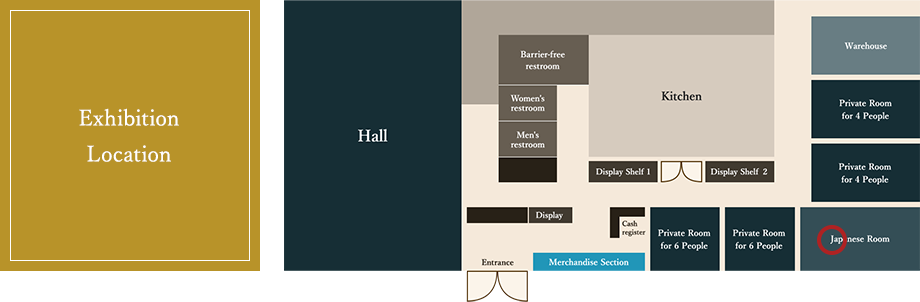

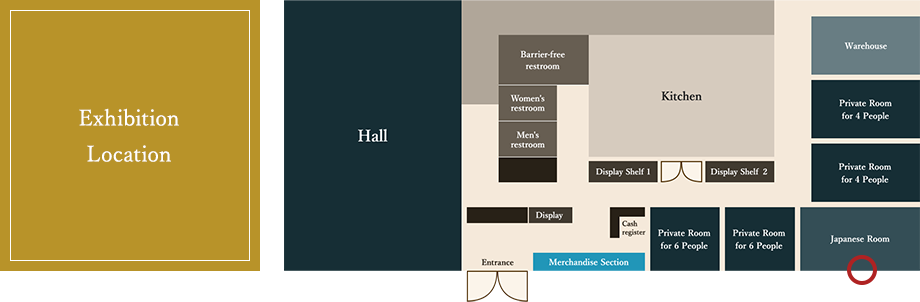

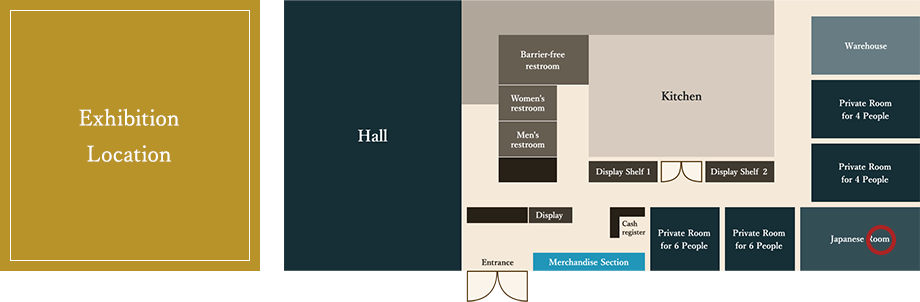

Features of Each Room at

Kojimachi NADAMAN Fukuoka Bettei

Each room has been meticulously designed so that you can fully enjoy dishes and conversation there.

-

Private Room for 6 People

We offer a calm space with a table and chairs made of materials from Fukuoka Prefecture.

It can be combined with the adjacent room for 6 persons to accommodate 12 persons. -

Japanese Room

Although the room has a laid-back atmosphere with tatami from Kakegawa, you can use a table and chairs.

The room affords ample space for up to 8 persons. -

Hall

This spacious room can be used as a reception or conference venue.

This room can be used for private events. -

Restroom

In addition to the restrooms for men and women, there is also a barrier-free restroom. The restrooms have a relaxing atmosphere.

Display Shelf

A wide variety of crafts from Fukuoka

Prefecture are displayed.

The current special exhibition features craftworks in “uguisu color,” the color of bush warbler feathers close to olive green, which matches the current season and the atmosphere of the restaurant. This is sure to be a feast for your eyes!

-

Pickup 01Hakata Doll

Pickup 01Hakata Doll

Hakata dolls are said to have been first made by tile craftsmen who served the Kuroda clan, the rulers of Fukuoka in the Edo period. These dolls are highly regarded both in Japan and abroad as a symbol of Japanese beauty.

-

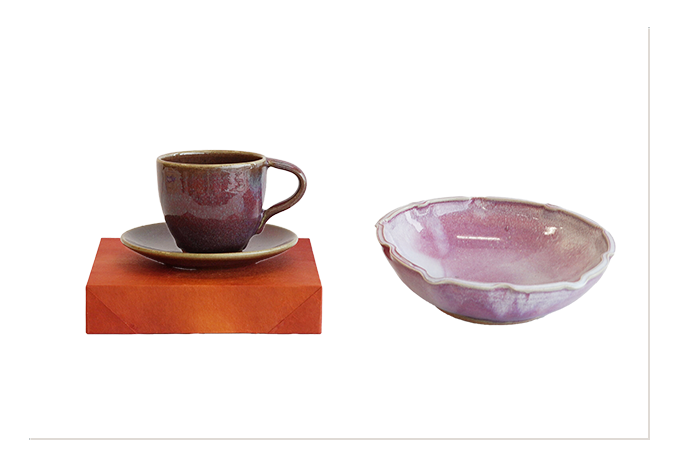

Pickup 02Agano Ware

Pickup 02Agano Ware

In the Edo period, Agano ware was highly valued as works of the kiln that served the Kokura Domain’s successive lords from the Hosokawa clan and then the Ogasawara clan. It was also treasured by tea ceremony masters as coming from one of the seven kilns loved by Kobori Enshu, a famous tea connoisseur. Agano ware is characterized by a unique depth created by beautiful glaze on thin and light clay.

-

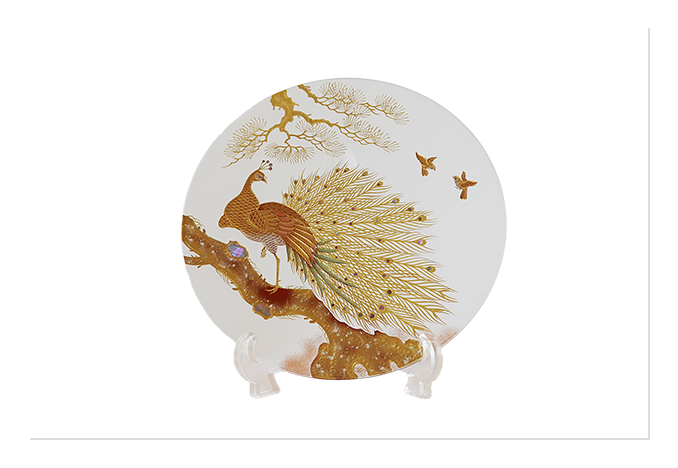

Pickup 03Kurume Okiage Doll

Pickup 03Kurume Okiage Doll

Okiage dolls are made by stuffing colorful fabrics with cotton and layering them one by one. They were first made by the wives of samurai of the Arima Domain in the Edo period, and subsequently produced in abundance up until the Meiji and Taisho periods, depicting gorgeous dolls and Kabuki actors.

-

Pickup 04Hakata Hariko Doll

Pickup 04Hakata Hariko Doll

Hakata Hariko dolls are made by pasting multiple layers of Japanese paper onto a wooden or plaster mold. They are popular as good luck charms with motifs such as tigers and daruma dolls.